Khushwant Singh observed, “Most men and women who deny God are to my knowledge more truthful, helpful, kinder and more considerate in their dealings with others that men of religion.” He was trying to probably say that lack of bigotry, fanaticism, and single-minded devotion to a God or a religion made people more open to accept the concepts of brotherhood and goodness of the human.

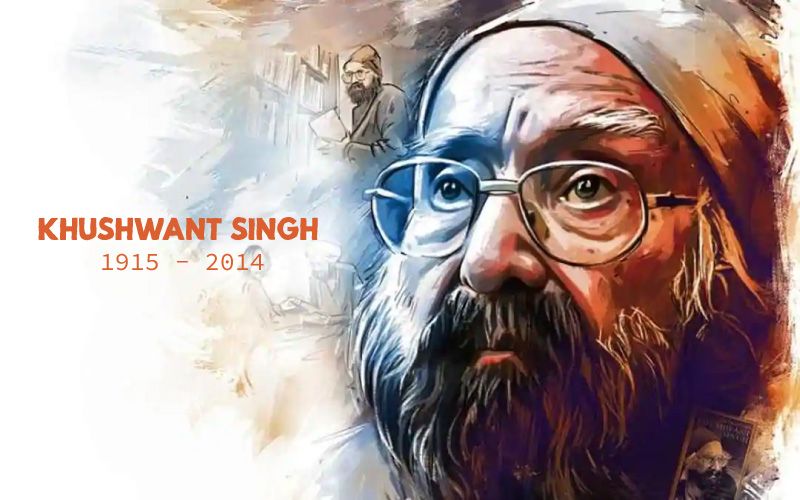

A Brief Reprise of Khushwant Singh’s Neo-Religion

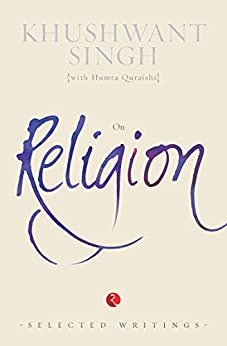

Khushwant Singh, the famous writer, was infamous in socio-religious circuits as a proclaimed agnostic. His intellectual mind continuously questioned the existence of God – the Creator, Preserver, Destroyer, and Supreme Judge – and of the proclaimed spiritual superiority of gurus and godmen. I have explored two of his writings on the subject – Agnostic Khushwant: There is No God and Gods and Godmen of India – and created a summary of his proposition of a new religion.

Born and brought up in a traditional Sikh family, Khushwant Singh was exposed to traditional nuances of religion and customs since his birth. In college, Khushwant’s fertile mind “began to question the value of these rituals.” At the same time, he read books of other religions and recognized common patterns and thoughts in major world religious philosophies. His thirsting heart absorbed the words and his inquisitive mind delved deeper into scriptures, but his soul remained uninspired by religion. “No religion evoked much enthusiasm in my mind. By the time India gained Independence on 15 August 1947, I had gained freedom from conformist religion and openly declared myself an agnostic.”

Yet, religion dominated Khushwant Singh’s life as he sought to meet men of religion, proclaimed spiritual gurus, religious practitioners, writers and followers on the subject, both in India and overseas. He grew to uphold the thoughts and philosophies of a few, like the teachings of the Brahma Kumaris, some of the ideas of Osho Rajneesh and His Holiness, The Dalai Lama, and the social service ethics of Mother Theresa. None could answer his question about the existence of God. He sought a scientific answer and rejected the theory of Karmic debt and the afterlife as non-scientific. He wrote, “Believers would have to fly across to God on the magic carpet of faith. We agnostics would like a solid, concrete bridge of reason to cross over from the known to the unknown.”

In his opinion, the world was seeking a God that was best described as the “Wadda Beparwah” else how could one explain the injustice, crime, poverty, unhappiness, illness, and lowly human conditions around the world? And when men’s prayers were unanswered by the Great Uncaring One, man resorted to rituals, practices, and communal prayer to stir the mercy of their Gods.

It is interesting to note that while Khushwant Singh denounced established religions and their concept of God; he was not against the concept of religion. He asserted that the current religions practiced around the world were obscure and failed to fulfill any purpose other than achieving material gains. He was in favor of starting a cult, a neo-religion that was based on individual goodness, social welfare, and a back to Nature theme.

Khushwant Singh observed, “Most men and women who deny God are to my knowledge more truthful, helpful, kinder and more considerate in their dealings with others that men of religion.” He was trying to probably say that lack of bigotry, fanaticism, and single-minded devotion to a God or a religion made people more open to accept the concepts of brotherhood and goodness of the human. His experiences showed that men of religion would commit sins – steal, lie, hurt others, even kill – in the name of religion and then go on a pilgrimage or ask forgiveness from their Almighty! It is the double-standards of men professing religiosity that never failed to amuse Khushwant Singh. The distortion of religious texts and of spiritual messages, to meet materialistic ends, remained his greatest grouch against men of religion and godmen.

His personal religious principles encompassed practical aspects like reducing the population and he endorsed harsh measures like sterilization after the birth of two children. He professed safeguarding nature, advocated planting trees and not felling trees to make houses and furniture. He spoke about abolishing the practice of cremation of the dead as it led to wastage of wood, and pollution of the holy rivers. He questioned observation of dietary rules, religious rituals and customs. He spoke openly against jagratas, satsangs, kirtans and chants over loudspeakers, religious processions, water immersion of idols, and religious individualism.

He wrote, “… major religious communities of India should strive so that various ethnic and other groups may live in peace and harmony.” He advocated cultivating true silence as a means of connecting with your inner thoughts. He wrote that the government should prohibit the building of any more places of worship, which often become the cause of idealistic and then violent conflict between religious communities. The doubting Sikh wondered how mortal gurus could be considered immortal by their followers, how people could believe in the afterlife without scientific proof, how godmen rivaled each other and amassed wealth, often illegally, and how they professed detachment and renunciation but themselves wallowed in luxury and worldly affairs.

Khushwant Singh rejected communal prayer with the belief that prayer was a purely personal experience. “… prayer has power to infuse self-confidence but it can, and its often, known to achieve wrong ends…. Prayers are best said in solitude and should be addressed to oneself.” He says, “…stare into your own eyes and ask yourself, “Did I wrong anyone today?”” Prayer does not create miracles but the reassurance to face adversities. Prayer offered with a pure heart and without a desire to bargain can be effective. Laughter and joy can have the power of prayer and looked on the home as the only “legitimate place of worship.”

He postulated a work-ethic based religion, where there was no place for holy men, sadhus, yogis and anyone who lived off the earnings of others, unless physically disabled to make an earning. Community worship should be replaced with one-hour of daily, mandatory, community service and ecological work. He rejected vanprastha and sanyas, for a healthy man must be compelled to work until his mind and body are able to do so. Yoga, according to him, helped to reduce stress and restore mental balance.

Khushwant’s journey in seeking God and a true Godman is actually the quest of each intelligent human being who follows the path of righteousness, goodwill, harmony, and seeks peace and quietude. His new religion is the religion of every genuine social activist, every animal lover, and each individual who finds solace in the solitude and the beauty of nature. The agnostic Khushwant Singh was in essence a pronounced conservationist and avid nature lover with a deep faith in the goodness of human beings, who he believed were misled by the selfish proclivities of religious bigots. His own life was an example in fulfillment of the belief – “… the best way to spend your life on earth is to create something worthwhile which may live after you; nothing of lasting worth can be created except by ceaseless striving triggered off by an ever-active talatum mind.” (Talatum is Urdu for continuously crashing waves).

It would be interesting to ask him if he believed that each man had the potential to a God, to be a Messiah, a Savior and a Prophet, to be the Great Charioteer and to be the Ideal Follower of Rules. He would probably swirl the question on his tongue with a sip of Scotch and ask, … “why not be honest and admit ‘I do not know’?”